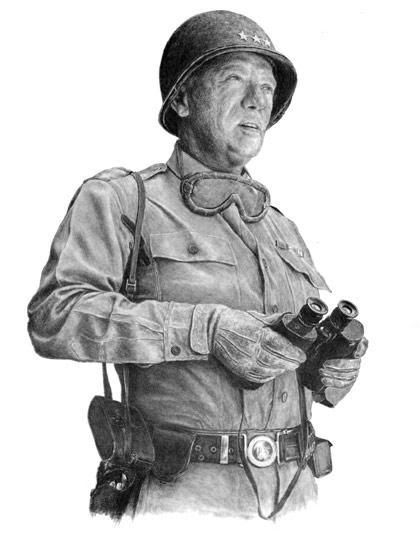

George Smith Patton GCB, Order of the British Empire (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945)

was a leading U.S. Army general in World War II in campaigns in North Africa, Sicily, France, and Germany, 1943–1945. In World War I he was a senior commander of the new tank corps and saw action in France. After the war he was an advocate of armored warfare but was reassigned to the cavalry. In World War II he commanded both corps and armies in North Africa, Sicily, and the European Theater of Operations. The popular image of "Old Blood and Guts" contrasts with certain historians' portrayal of Patton as a successful military leader, whose record reveals a lack of personal control and outspoken behavior.

Slapping incident and removal from command

Patton's bloodthirsty speeches resulted in controversy when it was claimed one inspired the Biscari Massacre, where American troops who followed his instructions to be ruthless were jailed after killing seventy-six prisoners of war, although Patton and their senior officers were not charged with any wrong-doing. A similar event is the Canicattì massacre which saw Sicilian civilians (including one 11 year old girl) killed by a group of soldiers ultimately under Patton's command.

Even worse for him was the "slapping incident", which occurred on August 3, 1943[6] that nearly ended Patton's career. The matter became known after newspaper columnist Drew Pearson revealed it on his November 21 radio program, reporting that General Patton had been "severely reprimanded" as a result.[7] Allied Headquarters denied that Patton had been reprimanded, but confirmed that Patton had slapped a soldier.

According to witnesses, General Patton was visiting patients at a military hospital in Sicily, and came upon a 24-year old soldier who was weeping. Patton asked "What's the matter with you?" and the soldier replied, "It's my nerves, I guess. I can't stand shelling." Patton "thereupon burst into a rage" and "employing much profanity, he called the soldier a 'coward'" and ordered him back to the front. As a crowd gathered, including the hospital's commanding officer, the doctor who had admitted the soldier, and a nurse, Patton then "struck the youth in the rear of the head with the back of his hand". Reportedly, the nurse "made a dive toward Patton, but was pulled back by a doctor" and the commander intervened. Patton went to other patients, then returned and berated the soldier again.[8]

When General Eisenhower learned of the incident, he ordered Patton to make amends, after which, it was reported, "Patton's conduct then became as generous as it had been furious," and he apologized to the soldier "and to all those present at the time,"After the film Patton was released in 1970, Charles H. Kuhl recounted the story and said that Patton had slapped him across the face and then kicked him as he walked away. "After he left, they took me in and admitted me in the hospital, and found out I had malaria," Kuhl noted, adding that when Patton apologized personally (at Patton's headquarters) "He said he didn't know that I was as sick as I was." Kuhl, who later worked as a sweeper for Bendix Corporation in Mishawaka, Indiana, added that Patton was "a great general" and added that "I think at the time it happened, he was pretty well worn out himself."[10] Kuhl died on January 24, 1971

As it turned out, Patton had slapped another soldier ten days earlier, though Kuhl's story was the one that received publicity.[12] Other reporters had decided to keep the incident quiet, and Kuhl's parents had avoided mention of the matter "because they did not wish to make trouble for General Patton,"[13]. Eisenhower thought of sending Patton home in disgrace, as many newspapers demanded. But after consulting with George Marshall, Eisenhower decided to keep Patton, but without a major command. Eisenhower used Patton's "furlough" as a trick to mislead the Germans as to where the next attack would be, since they assumed Patton would lead the attack and he was the general they feared the most. During the 10 months Patton was relieved of duty, his prolonged stay in Sicily was interpreted by the Germans to be indicative of an upcoming invasion of southern France. Later, a stay in Cairo was interpreted as heralding an invasion through the Balkans. German intelligence misinterpreted what happened and made faulty plans as a result.

In the months before the June 1944 Normandy invasion, Patton gave public talks as commander of the fictional First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG), which was supposedly intending to invade France by way of Calais. This was part of a sophisticated Allied campaign of military disinformation, Operation Fortitude. The Germans misallocated their forces as a result, and were slow to respond to the actual landings at Normandy.

In a story recounted by Professor Richard Holmes, just three days before D-Day, during a reception in the London Ritz Hotel, Patton shouted across a crowded reception in the direction of Eisenhower "I'll see you in Calais!", much to the consternation of all those around him. The ploy appears to have worked as reports of overnight troop movements North from Normandy were detected by Bletchley Park code decrypts.

Normandy

Following the Normandy invasion, Patton was placed in command of the U.S. Third Army, which was on the extreme right (west) of the Allied land forces. Beginning at noon on August 1, 1944, he led this army during the late stages of Operation Cobra, the breakout from earlier slow fighting in the Normandy hedgerows. The Third Army simultaneously attacked west (into Brittany), south, east towards the Seine, and north, assisting in trapping several hundred thousand German soldiers in the Chambois pocket, between Falaise and Argentan, Orne.

Patton used Germany's own blitzkrieg tactics against them, covering 60 miles in just two weeks, from Avranches to Argentan. Patton's forces were part of the Allied forces that freed northern France, bypassing Paris. The city itself was liberated by the French 2nd Armored Division under French General Leclerc, insurgents who were fighting in the city, and the US 4th Infantry Division. The French 2nd Armored Division had recently been transferred from the 3rd Army, and many soldiers of that Division thought they were still part of 3rd Army. These early 3rd Army offensives showed the characteristic high mobility and aggressiveness of Patton's units. Patton demonstrated an understanding of the use of combined arms by using the XIX Tactical Air Command of the Ninth Air Force to protect his right (southern) flank during his advance to the Seine.

Rather than engage in set-piece slugging matches, Patton preferred to bypass centers of resistance and use the mobility of US units to the fullest, defeating German defensive positions through maneuver rather than head-on fighting whenever possible. He was able to do this in part because of his systematic exploitation of ULTRA, a highly classified system that was very successful in reading German ENIGMA ciphers. Still, Patton was able to continue these tactics despite German radio silence during preparation for the Ardennes Offensive (Battle of the Bulge).

Lorraine

General Patton's offensive, however, came to a screeching halt on August 31, 1944, as the Third Army literally ran out of gas near the Moselle River, just outside of Metz, France. Berragan (2003) argues it was due primarily to Patton's ambitions and his refusal to recognize that he was engaged in a secondary line of attack. Others suggest that General John C.H. Lee, commander of the Zone of Communication, chose that time to move his headquarters to the more comfortable environs of Paris. Some 30 truck companies were diverted to that end, rather than providing support to the fighting armies.

Patton expected that the Theater Commander would keep fuel and supplies flowing to support successful advances. However, Eisenhower favored a "broad front" approach to the ground-war effort, knowing that a single thrust would have to drop off flank protection, and would quickly lose its punch. Still, within the constraints of a very large effort overall, Eisenhower gave Montgomery and his 21st Army Group a strong priority for supplies, to give him the chance to make the breakout that Montgomery claimed would end the war.

The combination of supply priority to Montgomery, and diversion of resources to moving the Communications Zone, coupled with Patton's refusal to attack slowly, resulted in the 3rd Army running out of gas in Alsace-Lorraine while exploiting German weakness.

Patton's experience suggested that a major US and allied advantage was in mobility. This led to a greater number of US trucks, higher reliability of US tanks, better radio communications, all contributing to superior ability to operate at a high tempo. Slow attacks were wasteful and resulted in high losses; they also permitted the Germans to prepare multiple defensive positions rather than withdraw from one defense to another after inflicting heavy casualties on US and allied forces. He refused to operate that way.

The time needed to resupply was just enough to allow the Germans to further fortify the fortress of Metz. In October and November, the Third Army was mired in a near-stalemate with the Germans, with heavy casualties on both sides. By November 23, however, Metz had finally fallen to the Americans, the first time the city had been taken since the Franco-Prussian War.

In late 1944, the German army made a last-ditch offensive across Belgium, Luxembourg, and northeastern France in the Ardennes Offensive (better known as the Battle of the Bulge), nominally led by German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. On December 16, 1944, the German army massed 29 divisions (totaling some 250,000 men) at a weak point in the Allied lines and made massive headway towards the Meuse River during one of the worst winters Europe had seen in years. It was during the midst of this fighting that the weather had become bitterly cold and snowy, which halted tank operations for a time.

Needing just one full day (24 hours) of good weather, Patton ordered the Third Army Chaplain, (COL) James O'Neill, to come up with a prayer beseeching God to grant this. The weather did clear soon after the prayer was recited, and Patton decorated O'Neill with the Bronze Star on the spot.[14] Following this, he continued ahead with dealing with the German offensive and von Rundstedt.

Patton turned the 3rd Army north abruptly (a notable tactical and logistical achievement), disengaging from the front line to relieve the surrounded and besieged 101st Airborne Division pocketed in Bastogne. By February, the Germans were in full retreat and Patton moved into the Saar Basin of Germany. The bulk of 3rd Army completed its crossing of the Rhine at Oppenheim on March 22, 1945.

Patton was planning to take Prague, Czechoslovakia, when the forward movement of American forces was halted. His troops liberated Pilsen (May 6, 1945) and most of western Bohemia.

No comments:

Post a Comment